Singing An Old Song

After my most recent column appeared, I ended up taking an unintentional sabbatical from writing. Teaching full-time while ushering my family through the winter holidays occupied most of my energy. Then, on New Year’s Eve, various members of our family began falling ill with what would become a cycle of every virus on the market. (I’m still not sure we’re completely in the clear, but we’re running out of germ options).

During this time, a Presidential election occurred. Now that I have enough bandwidth to lift my head and survey the terrain, I find that the landscape is depressingly familiar. Some people are triumphant, some are grieving, and nearly everyone is angry at someone else. Despite knowing better, mature adults can’t seem to resist posting polarizing items on social media; despite knowing better, other mature adults can’t seem to resist responding, and our divisions deepen and harden. It’s a difficult time for those who prioritize kind discourse and caring for others, who flinch at policies and rhetoric that seem designed to shock and divide further; these people stare at each other with desperate eyes and whisper, “What can we do? How can we help?”

We have been here before. Same song, second verse, a little bit louder and a little bit worse.

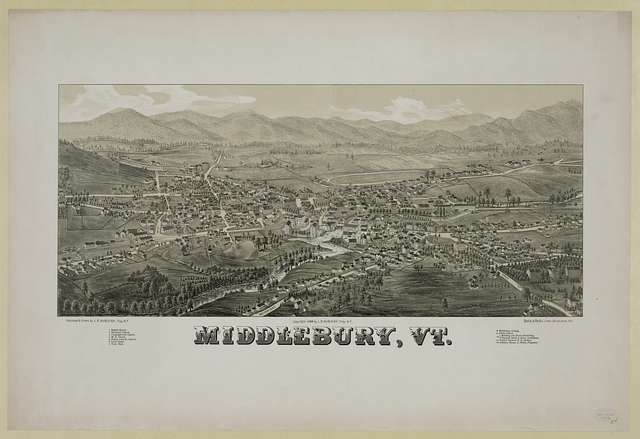

Of course, it’s not just the second verse: It’s an old, old song. I was reminded of this recently, when I took my children to New York City for February vacation to see the Broadway musical Hadestown, written by our Addison County neighbor, the brilliant Anais Mitchell.

Hadestown is a retelling of the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Mitchell portrays Orpheus’s attempt to rescue his beloved Eurydice from Hades’s underworld as a struggle of art, beauty, and love against the forces of death, industrialization, and power. Mitchell re-tells the myth faithfully rather than concocting a Disney-fied happy ending, which is to say: death, industrialization, and power win in the end.

Or do they?

Click here to continue reading this week’s “Faith in Vermont” column in The Addison Independent.